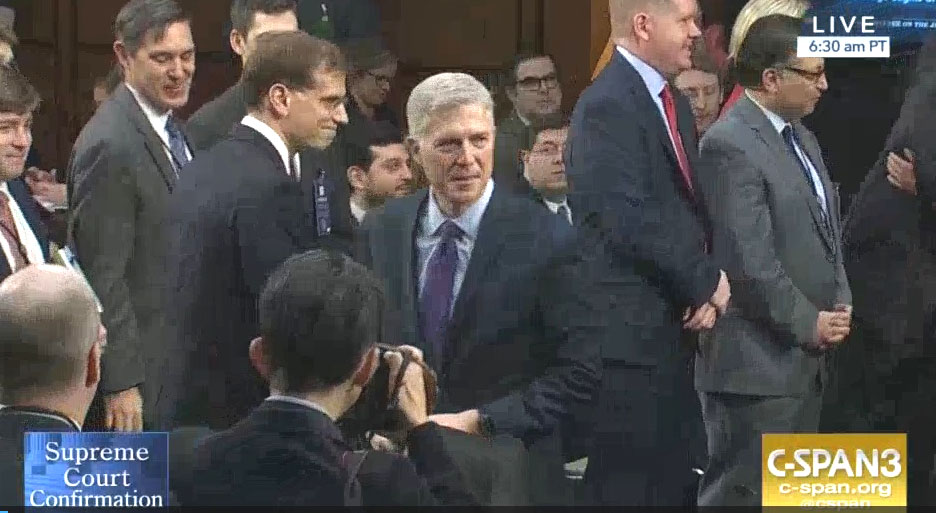

WASHINGTON (BP) — Neil Gorsuch steadfastly refused to provide judge-like commentary on such issues as abortion and assisted suicide in his confirmation hearings but was not reluctant to explain his ruling in a vital religious liberty case.

President Trump’s nominee to the U.S. Supreme Court answered questions about his role in supporting the free exercise of religion rights of Hobby Lobby Tuesday (March 21) as a member of the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver. Gorsuch responded to questions about the religious liberty case from both Democrats and Republicans during 10 hours of questioning by the 20 members of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

President Trump’s nominee to the U.S. Supreme Court answered questions about his role in supporting the free exercise of religion rights of Hobby Lobby Tuesday (March 21) as a member of the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver. Gorsuch responded to questions about the religious liberty case from both Democrats and Republicans during 10 hours of questioning by the 20 members of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Gorsuch — who has served on the 10th Circuit Court for more than 10 years — freely offered his view of an opinion he participated in. He declined, however, several opportunities to comment on issues, including abortion and physician-assisted suicide, he has yet to rule on and may appear in cases before him in the future.

On April 3, the Judiciary Committee is expected to send Gorsuch’s nomination to the full Senate, where the central question would appear to be whether Republicans have enough votes to overcome an expected Democratic filibuster. The GOP majority has 52 members, but 60 votes are required to halt a filibuster and vote on confirmation. If the GOP falls short, it can hold a vote to change the rules and confirm Gorsuch by a simple majority.

The 10th Circuit Court, with Gorsuch writing a concurring opinion in the majority, ruled in favor of Hobby Lobby in 2013 in the arts and crafts chain’s challenge to the Obama administration’s abortion/contraception mandate. The mandate required employers to provide coverage for contraceptives that can potentially cause abortions. The next year, the Supreme Court affirmed the appeals court opinion, upholding objections by “closely held,” for-profit companies such as Hobby Lobby, which is owned by the Green family.

In response to Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, Gorsuch agreed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), a 1993 federal law at the heart of the case, protects individuals with minority religious beliefs as much as for-profit corporations owned by evangelical Christians.

RFRA — which requires the government to have a compelling interest and use the narrowest possible means in burdening a person’s religious exercise — also “applies to Little Sisters of the Poor [a Roman Catholic order of nuns that serves the needy] and protects their religious exercise,” Gorsuch said.

In addition, the 10th Circuit “held [RFRA] applied to a Muslim prisoner in Oklahoma who was denied a halal meal,” Gorsuch told Hatch. “It’s also the same law that protects the rights of a Native American prisoner who was denied access to his prison sweat lodge, it appeared, solely because of a crime he committed, and it was a heinous crime. But it protects him too. I wrote the [opinion in the] Native American prisoner case and wrote a concurrence in the Muslim case.”

President Clinton signed RFRA into law after a broad coalition of religious freedom advocates — including the Southern Baptist Christian Life Commission, now the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission (ERLC) — pushed for the measure in response to a heavily criticized Supreme Court decision and following nearly unanimous approval by Congress.

Steven Harris, the ERLC’s director of advocacy, told Baptist Press, “Judge Gorsuch has consistently demonstrated a robust and insightful understanding of religious liberty in America.

“Throughout his comments during confirmation hearings, I was encouraged by his willingness to address the issue head-on,” Harris said in written comments, “and I believe that such is indicative of his commitment to the laws of religious liberty that undergird our democracy.”

Some Democratic committee members challenged Gorsuch’s opinion — and that of the 10th Circuit majority — that RFRA protects the religious free exercise of for-profit businesses.

With RFRA, “Congress was dissatisfied with the level of protection afforded by the Supreme Court under the First Amendment to religious exercise,” disagreeing with the late Associate Justice Antonin Scalia’s opinion in a 1990 case, Gorsuch told Sen. Richard Durbin, D-Ill. As a result, Congress drafted — and approved — “a very, very strict law, and it says that any sincerely held religious belief cannot be abridged by the government without a compelling reason and even then it has to be narrowly tailored, strict scrutiny, the highest legal standard in American law,” he said.

“Hobby Lobby came to court and said, ‘We deserve protections too,'” Gorsuch recalled for Durbin. “We looked at the law, and it says any person with a sincerely held religious belief is basically protected…. What does ‘person’ mean in that statute? Congress didn’t define the term. So what does a judge do? … He goes to the Dictionary Act [a law that defines terms when they aren’t otherwise defined], and [in] the Dictionary Act, Congress has defined person to include corporation. So you can’t rule out the possibility that some companies can exercise religion.”

The Supreme Court agreed the federal government had a compelling interest, so the question became whether the Obama administration’s action was “narrowly tailored” regarding the Green family’s objections, he said.

“And the answer there the Supreme Court reached in precedent binding on [the 10th Circuit] now, and we reached in anticipation, is: No, that it wasn’t as strictly tailored as it could be because the government had provided different accommodations to churches and other religious entities,” Gorsuch said. “[T]he government had accommodated that with respect to other religious entities and couldn’t provide an explanation why it couldn’t do the same thing here.”

Gorsuch told Durbin, “Now Congress can change the law … eliminate RFRA all together. It could say that only natural persons have rights under RFRA. It could lower the test on strict scrutiny to a lower degree of review if it wished.

“[I]f we got it wrong, I’m sorry,” he said. “But we did our level best, and we were affirmed by the United States Supreme Court.”

Michael Whitehead — a Southern Baptist lawyer in Kansas City whose practice focuses on religious liberty and nonprofit organization law — said Democratic senators “seem to have ‘buyer’s remorse’ about RFRA.”

“A nearly unanimous Congress passed the bill, and it was proudly signed by President Clinton in 1993,” Whitehead, who was the Christian Life Commission’s general counsel at the time, said in a written statement for BP. “Today they act like they were tricked into adopting it, and they wish they could rewrite it to exclude firms like Hobby Lobby.

“As Judge Gorsuch instructed them, Congress made the law, and Congress can change the law, but the Supreme Court has now interpreted the law to include firms like Hobby Lobby, upholding the definition used by Judge Gorsuch and the 10th Circuit majority,” Whitehead said.

On abortion, Gorsuch declined to comment on the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that legalized abortion.

Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., asked Gorsuch about the first time he met Trump before his nomination: “In that interview, did [Trump] ever ask you to overrule Roe v. Wade?”

“No, senator,” Gorsuch replied.

“What would you have done if he had asked?” Graham said.

“Senator, I would have walked out the door,” the nominee responded. “That is not what judges do. They don’t do it at that end of Pennsylvania Avenue [at the White House] and they shouldn’t do it at this end [at the Capitol] either, respectfully.”

Regarding physician-assisted suicide, Gorsuch responded to questions about a book he wrote on the subject before he became a judge. The 2006 book, “The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia,” argues against legalization of the end-of-life practices. He was speaking as a commentator, not a judge, at the time, he told committee members.

He agrees with the Supreme Court’s companion rulings in 1997 that left the legalization of assisted suicide with the states.

In his book, Gorsuch told Sen. Chris Coons, D-Del., he was concerned what legalization “might mean for the least amongst us, the most vulnerable, the disabled, the elderly who might be pressured into accepting an early death because it’s a cheaper option than more expensive hospice care.”

Trump nominated Gorsuch, 49, to the high court in late January, nearly a year after the death of Scalia. Like Scalia, Gorsuch espouses a philosophy and record of interpreting the Constitution and laws based on its original meaning and their text, respectively.

The ERLC sponsored a letter Feb. 1 in which more than 50 Southern Baptist and other evangelical leaders called for confirmation of Gorsuch. The signers said they believe Gorsuch’s judicial philosophy meets the thresholds of their “core social principles.” Those precepts include in the Supreme Court’s purview “the protection of the unborn, the strengthening of religious liberty, and a dedication to human flourishing – which we believe can only be accomplished by a biblical definition of marriage and family,” they said.