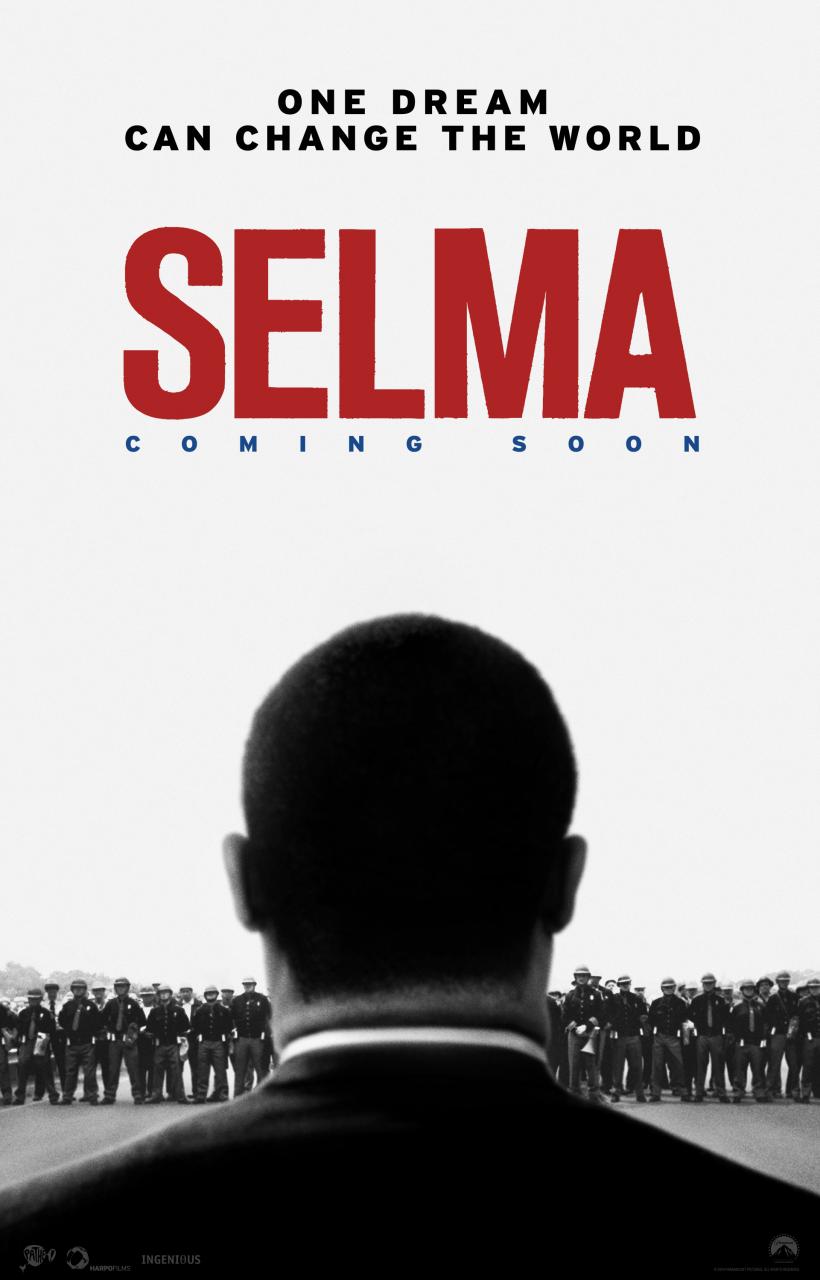

NASHVILLE (BP) — The movie “Selma” opening today nationwide can initiate honest racial reconciliation discussion and the study of African American history among Southern Baptists, said Chris McNairy, a consultant who has helped Mississippi Baptists bridge racial barriers the past two years.

McNairy said the film, though it takes artistic license highlighting the 1965 “Bloody Sunday” march across Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., can encourage Southern Baptists of all ethnicities to study the facts of the historic struggle for voting rights by African Americans in the 1960s South.

McNairy said the film, though it takes artistic license highlighting the 1965 “Bloody Sunday” march across Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., can encourage Southern Baptists of all ethnicities to study the facts of the historic struggle for voting rights by African Americans in the 1960s South.

“The movie brings out that point that there is a history that we cannot throw away,” said McNairy, founder of Urban Fusion Network, focused primarily on urban missions in spreading the Gospel and enhancing Christian disciple-making.

“For some of us evangelical conservatives, we don’t want to talk about parts of American history,” McNairy said. “Not to make a comparison to Jewish life, but for every diaspora there’s a part of their history that if we’re honest about it, we want to say, ‘We shall never forget.’

“The Jewish Diaspora will say they will never forget the internment camps. For the African Diaspora, they will never forget the slave trade and slavery. And you can go through the six major diasporas in America and they all have something about their history that they don’t want forgotten,” McNairy said. “The problem with historical segmentation in America is that it’s all about the European Diaspora. When we look at history, there’s not much dealing with the nonwhite history, so that even nonwhites don’t know nonwhite history.”

Selma, which first opened in a limited U.S. release on Christmas Day, has already spurred racial reconciliation talks in key sites of racial conflict in the country. In Sanford, Fla., where George Zimmerman killed Trayvon Martin in 2012, two pastors have used the movie to give new life to racial reconciliation talks there.

In New York, African American business leaders have raised enough money for 27,000 middle school students to attend free viewings of Selma. The movement #SelmaHandinHand is encouraging interdenominational Selma viewings and post-viewing discussions in theaters across the country. The movement’s Twitter page shows participation in various states, including Alabama and Virginia. In Philadelphia, the National Liberty Museum is sponsoring a Selma Speech & Essay Contest among high school students, with a $5,000 grand prize.

Jay Wolf, pastor of First Baptist Church of Montgomery, Ala., affirmed the movie as a good discussion-starter for racial reconciliation.

In Montgomery, he said, “we’ve been engaged in this conversation regarding racial reconciliation linked to revival for two decades. We pray that the movie and the Voters Rights March [50th] Anniversary will be a catalyst for the body of Christ to live, love and personify the call of Jesus to be one so the world may believe.”

Wolf, as a longtime advocate of racial reconciliation, has sought to develop a culture of inclusion through First Baptist, a congregation of 4,600.

“Over 20 years ago a group of black and white ministers began to meet under the banner of John 17:21. Our goal is spiritual awakening. Since God’s empowering Spirit cannot move over broken lines we wanted to be connected,” Wolf said. “John 17:21 is the prayer of Jesus asking that ‘we become one so that the world will believe.’ Our disunity and disconnection discounts our evangelism.

The Alabama Baptist State Convention also has worked to bridge racial divides, forming an inter-Baptist fellowship of black and white Baptists and cross-cultural conferences including African Americans, whites, Hispanics and Asians, said Rick Barnhart, a state missionary and director of the Alabama Baptist office of associational missions and church planting.

In Mississippi, McNairy has worked on a contract basis with Baptists to build new Gospel-centered collaborations across the state. While Mississippi has the highest percentage of African Americans of any state in the union, at nearly 40 percent, only 40 of its 2,000-plus Southern Baptist churches are majority black.

Evidence of the progress Mississippi Baptists have made is the election of the convention’s first African American officer, Larry Young, pastor of Spangle Banner Missionary Baptist Church in Pace, who was elected as second vice president during last fall’s 2014 annual meeting.

Mississippi Baptists have held table talks and roundtable discussions on race relations around the state and will host the “Can We Talk? Mississippi Black Church Leadership Conference” July 16–18 to focus on racial reconciliation, Gospel collaboration and missional disciple making, McNairy said.

“While it’s intended for Mississippi, we’re opening it up to whosoever will, and it’s being hosted by Morrison Heights Baptist Church, which is an overwhelmingly white SBC church. But that’s the venue we wanted because we’re hoping and praying and working toward 1,000 people in attendance,” McNairy said. “We’re moving toward a full-blown conference menu that won’t end with just equipping and conversation, but moves toward action.”

Selma comes a week shy of the Martin Luther King Jr. national holiday, and in the 50th anniversary year of the voting rights march. But the movie has come with controversy.

Mark K. Updegrove, director of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum, and Joseph A Califano Jr., President Johnson’s top assistant for domestic affairs from 1965-69, have both charged that the movie unfairly portrayed LBJ’s role in the voting rights struggle. Additionally, the movie does not include King’s exact words but paraphrases because of copyright issues.

Ava DuVernay, director of the movie, has described Selma as a dramatization of the events, not a documentary.

“What’s important for me as a student of this time in history is to not deify what the president did. Johnson has been hailed as a hero of that time, and he was, but we’re talking about a reluctant hero,” DuVernay was quoted as saying in Rolling Stone magazine, referencing the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Johnson “was cajoled and pushed, he was protective of a legacy — he was not doing things out of the goodness of his heart,” DuVernay told the magazine. “Does it make it any worse or any better? I don’t think so. History is history and he did do it eventually. But [in respect to the purpose of the movie] there was some process to it that was important to show.”