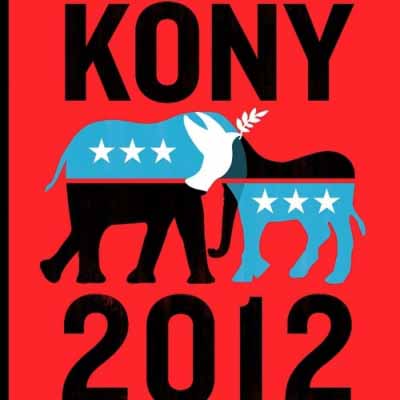

WASHINGTON (BP) — In the week since Invisible Children released its “Kony 2012” video online, the 30-minute video against the Lord’s Resistance Army has racked up more than 100 million views — beating out Lady Gaga, the “Laughing Baby,” and Susan Boyle, as the most viral video in history.

The film is a slick production calling for an end to the Ugandan rebel movement and its leader Joseph Kony, who has conscripted more than 30,000 children in the last 26 years to fight for his cause. It calls viewers to action, encouraging them to donate to Invisible Children and spread the word so Kony can be captured before the year’s end.

The film is a slick production calling for an end to the Ugandan rebel movement and its leader Joseph Kony, who has conscripted more than 30,000 children in the last 26 years to fight for his cause. It calls viewers to action, encouraging them to donate to Invisible Children and spread the word so Kony can be captured before the year’s end.

But during the past week, dozens of activists, journalists, and writers have criticized the campaign, questioning Invisible Children’s financial practices and the factual accuracy of the video.

One of the loudest criticisms focuses on Invisible Children’s spending, pointing out that more of the money it raises goes to creating films than actually to helping Ugandans. The group’s financial records show that it spends only 37 percent of its budget on central African-related programs, while 20 percent go to salaries and overhead and 43 percent to the awareness program.

Jedidiah Jenkins, Invisible Children’s director of ideology, doesn’t shy away from the emphasis on awareness: “The truth about Invisible Children is that we are not an aid organization, and we don’t intend to be,” he told GOOD Magazine. “…People think we’re over there delivering shoes or food. But we are an advocacy and awareness organization.”

While the video has increased awareness of child soldiers and Kony, critics question whether the information remains relevant.

Ugandan journalist Angelo Izama, a Knight Fellow at Stanford University, says the conflict discussed in the video is dated, with most of the footage from the height of the situation in 2003 and 2004. He points out that Kony and most of his army moved out of the country in 2006, and while they are still active in South Sudan and the Central African Republic, their numbers have dwindled to the hundreds.

“The filmmakers were going for an emotive response, and they have it,” Izama said, referring to the film’s scenes from 2003 of children huddling in a building, running from the LRA (Kony’s “Lord’s Resistance Army”), and an interview with a former child soldier, crying at the loss of his brother.

While the video calls for greater American intervention, not much more can be done without danger to the area and child soldiers, critics says. The Ugandan military has pursued the LRA since 2006, with little success. President Barack Obama sent 100 U.S. Army advisers to join the hunt last October.

In response to the criticism, Invisible Children notes that the film is “a first entry point to this conflict for many.” It also points to the resources it provides for supporters to learn more about the issue. One such resource, the LRA Crisis Tracker website launched in 2011, supplies verified information about the LRA’s recent movements and attacks.

Many African critics disagree with the campaign in general, arguing that it propagates the image of the helpless African victim. They argue that the video — and the conversation that it sparked — should include solutions provided by local sources.

“It calls upon an external cadre of American students to liberate them by removing the bad guy who is causing their suffering,” Ethiopian writer and activist Solome Lemm wrote in her blog. “Well, this is a misrepresentation of the reality on the ground. Fortunately, there are plenty of examples of child and youth advocates who have been fighting to address the very issues at the heart of IC’s work.”

Invisible Children says it works with local partners in Uganda and supports projects that it identifies as priorities. According to the group’s website, 95 percent of its leadership and staff on the ground are “Ugandans on the forefront of program design and implementation.”

–30–

Jordan Lee and Angela Lu write for World News Service, where this story first appeared.