BALTIMORE (BP)–Some call her “indefatigable.” John Roberts calls her “indomitable.”

Roberts is pastor emeritus of Woodbrook Baptist Church, formerly known as Eutaw Place Baptist Church, where Annie Walker Armstrong spent three-fourths of her life in ministry.

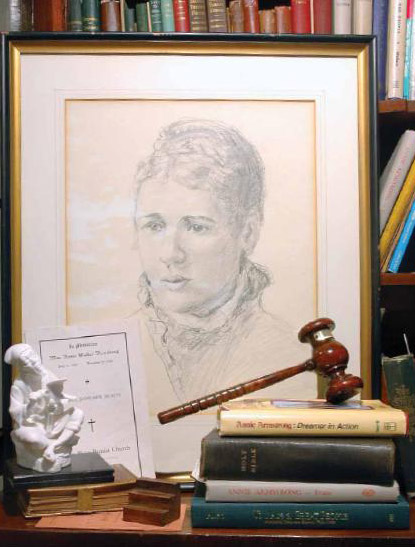

Beginning his ministry at Eutaw Place in 1959, Roberts followed Armstrong’s pastor, W. Clyde Atkins, in the pastorate. Though he never met the woman who is the namesake of the annual Annie Armstrong Easter Offering for North American Missions, her legacy has left an impact on his church, on Baltimore, and beyond.

Who is this indomitable Annie Armstrong?

Born in 1850 in the industrial port city of Baltimore, Armstrong, or “Miss Annie” as she was affectionately known, attended Seventh Baptist Church, which at the time met at Paca and Saratoga streets (the current site of the Shrine of Saint Jude).

At Seventh, Armstrong was baptized at the age of 19 and shortly thereafter joined more than 100 members from Seventh to pioneer a new work — Eutaw Place Baptist Church — at Eutaw Place and Dolphin Street. There, Armstrong remained an active member for nearly 70 years until her death in 1938.

Describing Armstrong as “a tall, stately, outspoken, strong-willed leader,” author Bobbie Sorrell credits Armstrong’s Harvard-educated pastor, Richard Fuller, for building her deep convictions about missions.

With his preaching described as “logic on fire,” Fuller’s passionate southern lawyer roots paved way for his influence in framing the Southern Baptist Convention; he preached its first annual sermon. Fuller thus gave Armstrong and others an insider’s view into the birth of the denomination.

At the local church level, Armstrong taught in the Infant class (also called the Primary Department, for children up to age 12) for 50 years. All the while, she maintained an interest in ministering to mothers, immigrants, the underprivileged, the sick, African Americans, Indians and, later in life, her Jewish neighbors.

Accordingly, she worked at the Home of the Friendless, where she served on the board of managers for more than 20 years.

She started the Ladies’ Bay View Mission, at the site of today’s Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, which was formerly known as Baltimore City Hospital.

Armstrong’s ties to Baltimore were even more numerous. Her great-great-great grandfather was Henry Sater, who built the first known Baptist church in Maryland. A childless widower at 50, Sater later married Dorcas Towson, of the family whose name lives on in the community of Towson, who became Armstrong’s great-great-great grandmother.

Like most Baltimoreans, Armstrong lived in row homes — on North Calvert Street with her parents James Dunn and Mary Elizabeth Armstrong and later on McCullough Street when her father died. In her elder years, she moved to Cecil Apartments, which adjoin Eutaw Place Baptist Church.

Not only did Armstrong embrace Baltimore with the love of Christ, but her reach also extended to the uttermost parts of the world. Most notable are her efforts in missions education and missions support.

In 1880, in her first prominent leadership position, Armstrong served as the first president of the Woman’s Baptist Home Mission Society of Maryland, which involved women in supporting the Home Mission Board (now North American Mission Board) of the Southern Baptist Convention. The society’s first priority locally was forming an Indian school and ministering to Chinese immigrants. The organization also provided support for work in Cuba and New Orleans.

Armstrong later became the corresponding secretary of the Maryland Mission Rooms, later called the Mission Literature Department, SBC. This department served as a missions library and reading room and ultimately became a publisher and distributor of missions literature.

Beginning in 1888, Armstrong led in framing the constitution of the Woman’s Missionary Union (WMU), an auxiliary to the Southern Baptist Convention. She served as corresponding secretary — a position equivalent to executive director today — until 1906, always refusing a salary for the work she did through WMU to further the Gospel.

Without today’s technology, Armstrong wrote letters by hand to all the Southern Baptist foreign societies. On one occasion, she asked them to contribute to the first Christmas offering, which resulted in enough money to send three — not one, as had been hoped — missionaries to assist Lottie Moon in China.

The Lottie Moon Christmas Offering for Foreign Missions, so named at Armstrong’s recommendation, has raised more than $2.6 billion for overseas missions to date.

In 1895, Armstrong led the WMU to contribute $5,000 to help alleviate the Home Mission Board’s $25,000 debt and prevent the withdrawal of missionaries from their mission fields. In response, WMU instituted the Week of Self-Denial as a time of praying for and giving to home missions. Since that time, a week of prayer and a home missions offering have continued. In 1934, the offering was named the Annie Armstrong Offering.

To date, the annual Annie Armstrong Easter Offering for North American Missions has generated more than $1.1 billion.

Armstrong also assisted organizations for Negro Baptist women and children and published literature for them.

“To me, Miss Armstrong was a symbol -– a marvel at what a woman could do. She fired my soul,” wrote Nannie Burroughs, corresponding secretary of the Woman’s Convention, auxiliary to the National Baptist Convention.

Year after year, Armstrong came up with new ways to get missions information out to the churches, to stir up missions efforts and to raise more prayer support and money for missions. In her later years, she took up the cause of the Church Building and Loan fund, enabling struggling congregations to build a church home.

Armstrong resigned from WMU in 1906 in opposition to the inclusion of WMU’s training school with a men’s seminary in Louisville, Ky. It was her belief that the organization could not devote attention to missions and women’s work in churches while raising funds to manage a school. She also disagreed with the establishment of a salary for the organization’s officers.

Armstrong died in 1938, the year of WMU’s 50th anniversary. She was buried at Greenmount Cemetery in Baltimore, in the same cemetery as John Healey, the Second and Fourth Baptist Church pastor who started the first Sunday School in this country and Richard Fuller.

How did she do it all? Roberts, Woodbrook’s pastor emeritus, asked the same question.

Those who knew Armstrong personally told him she had an intense prayer life that gave her real spiritual energy.

“It comes down to dedication, to doing your best in every category of ministry, with dedication, energy and prayer support,” Roberts also noted, recalling an adage of Fuller, who resolved “never to insult the Master with indolent preparation or superficial and ineffectual performance.”

“Fuller’s high standards surely influenced Miss Annie,” Roberts said.

That quality of Christian service shouldn’t be misunderstood as elitism, but instead should stress the importance of using all our faculties to do the very best for the Lord, Roberts said.

“Through her steadfast prayer, her focused determination and her willingness to put her faith into action, Annie Armstrong modeled for us the difference one person can make when she is obedient to allow God to work through her,” said Bob Reccord, current president of the North American Mission Board.

“So much of the International Mission Board’s work depends on the generous and faithful giving of Southern Baptists to the Lottie Moon Christmas Offering, and we have Annie Armstrong to thank for creating the offering,” agreed Jerry Rankin, president of the International Mission Board. “Annie’s legacy to the IMB began with a single missionary, Lottie Moon, and today, because of her tireless effort and passion for reaching the lost, the number of missionaries overseas has grown to more than 5,000.”

One of Armstrong quotes still inspires: “The future lies all before us … shall it only be a slight advance upon what we usually do? Ought it not to be a bound, a leap forward, to altitudes of endeavor and success undreamed of before?”

–30—-