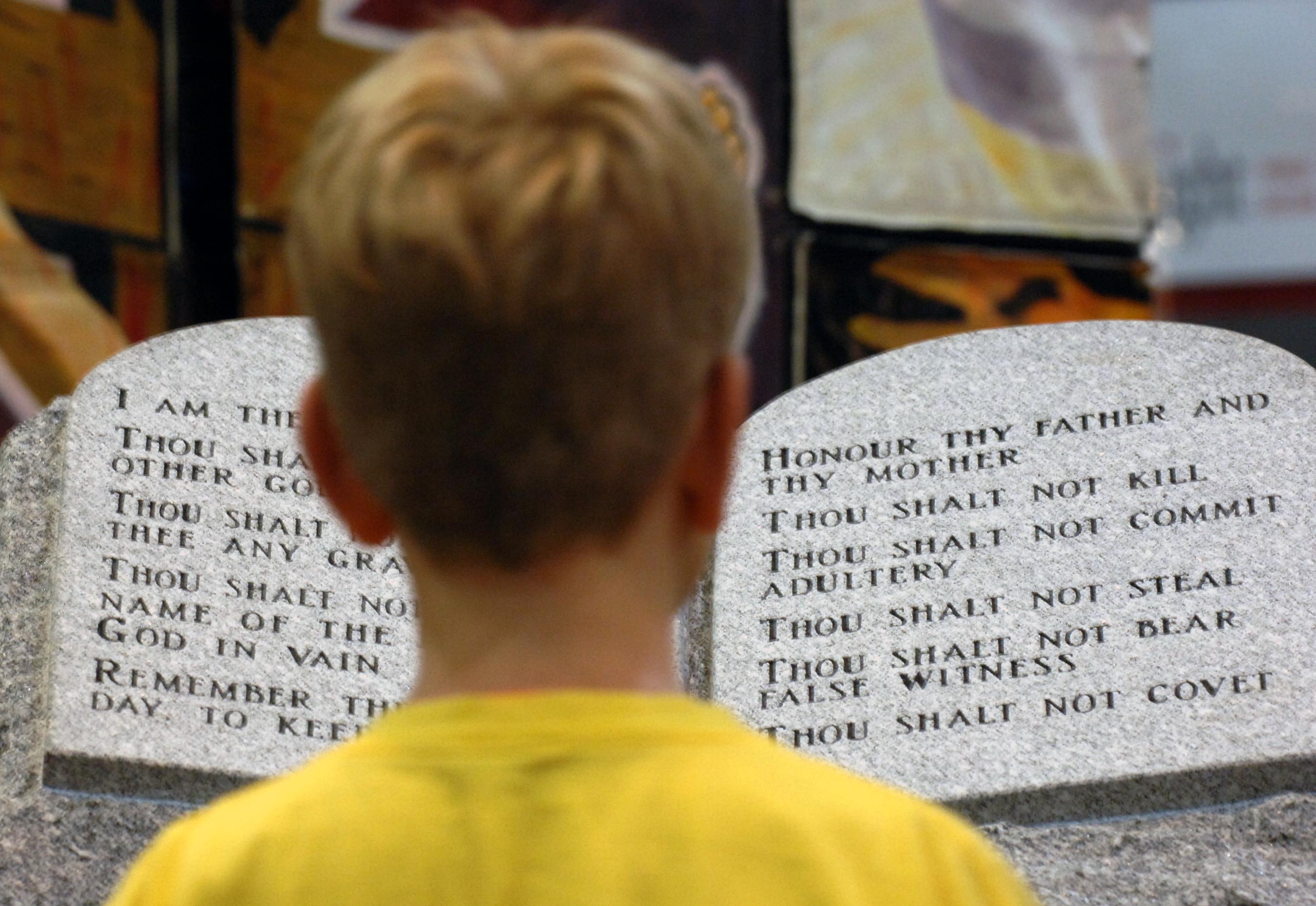

WASHINGTON (BP)–The U.S. Supreme Court continued its divisive, oft perplexing decision-making on the relationship between church and state June 27, invalidating Ten Commandments displays in Kentucky courthouses while upholding a monument of the Decalogue on the Texas capitol grounds.

The justices issued both 5-4 opinions on the final day of their term. They did so as the White House, Senate and many advocacy organizations awaited word of a possible retirement by a member of the high court. Chief Justice William Rehnquist, who has been undergoing treatment for thyroid cancer, and Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor have been mentioned most often as possible retirees. No justice made such an announcement in the court’s final session, however.

The highly anticipated rulings in the Ten Commandments cases again found the high court seeking to discern if an action sponsored by or permitted by the government violates the First Amendment’s ban on establishment of religion.

The court ruled Ten Commandments displays in courthouses in Kentucky’s McCreary and Pulaski counties violated the establishment clause, even though they were set among documents that included the Declaration of Independence, Bill of Rights and Magna Carta. The justices, however, decided a stand-alone, granite monument on the state capitol grounds in Austin, Texas, was constitutional.

While they applauded the Texas ruling, supporters of government accommodation of religion largely expressed disappointment with the decisions.

Southern Baptist church-state specialist Richard Land said he expected the court to “rule against a display by a government entity and accommodate a display by a nongovernmental group on government property.”

“The most alarming thing about this pair of rulings is that the decision to accommodate a Ten Commandments display donated by a nongovernmental source only won 5-4, which shows the degree to which this court has embraced secular fundamentalism as its religion,” said Land, president of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission. “The Kentucky courthouse decision shows that, as Justice [Antonin] Scalia said in the 2003 Lawrence v. Texas opinion [striking down state anti-sodomy laws], the majority of this court has ‘taken sides in the culture war,’ and it’s the side of secular fundamentalists.”

James Dobson, chairman of Focus on the Family, said the rulings send “a mixed message” to Americans. “The court has failed to decide whether it will stand up for religious freedom of expression, or if it will allow liberal special interests to banish God from the public square,” Dobson said in a written statement.

Supporters of strict separation between church and state were not totally satisfied either.

Barry Lynn, executive director of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, said the rulings produced a “mixed verdict, but on balance it’s a win for separation of religion and government.”

“Public buildings belong to everyone,” Lynn said in a written statement. “America is a diverse country, and our government should not send the message that some faiths are preferred over others. Public buildings should display the Bill of Rights, not the Ten Commandments.”

The justices issued the rulings from a building that contains carvings of Moses and the Ten Commandments both on the inside and outside. In fact, the Ten Commandments are displayed in thousands of government settings throughout the country.

In the Kentucky case, McCreary County v. ACLU of Kentucky, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled the Decalogue display violated the establishment clause. Meanwhile, the Fifth Circuit decided in Van Orden v. Perry there was no such violation in the monument on the Texas capitol grounds. A private organization, the Fraternal Order of Eagles, donated the six-foot-tall monument to the state in 1961.

In the court’s McCreary opinion, Associate Justice David Souter said the history of the Ten Commandments displays, which stood alone before they were twice changed to include other documents, should be considered in determining their constitutionality. Even the final display had a “predominantly religious purpose,” Souter wrote.

Though Souter acknowledged the Ten Commandments have influenced the American legal system, he said the “original text viewed in its entirety is an unmistakably religious statement dealing with religious obligations and with morality subject to religious sanction. When the government initiates an effort to place this statement alone in public view, a religious object is unmistakable.”

Scalia wrote the dissenting opinion, calling the court’s assertion government cannot favor religion over irreligion a “demonstrably false principle.” He said the McCreary opinion serves to “ratchet up the Court’s hostility to religion.”

The majority went beyond the oft-criticized Lemon test in “shifting the focus of Lemon’s purpose prong from the search for a genuine, secular motivation to the hunt for a predominantly religious purpose,” Scalia wrote. “Those responsible for the adoption of the Religion Clauses would surely regard it as a bitter irony that the religious values they designed those Clauses to protect have now become so distasteful that if they constitute anything more than a subordinate motive for government action they will invalidate it.”

The Lemon test has guided the high court’s decision-making in such cases since it was outlined in the 1971 Lemon v. Kurtzman opinion. According to the test, a government does not establish religion if its action has a secular purpose, does not promote or inhibit religion and does not entangle government excessively with religion.

Joining Souter in the majority were O’Connor and Associate Justices John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer.

Rehnquist, as well as Associate Justices Anthony Kennedy and Clarence Thomas, joined Scalia in dissenting.

In the Texas case, Breyer shifted sides to establish a majority with Rehnquist, Scalia, Kennedy and Thomas.

Writing for the majority, Rehnquist acknowledged the monument “has religious significance.” He called the inclusion of the Ten Commandments in a group of monuments on the capitol grounds a “passive use.” The display “has a dual significance, partaking of both religion and government,” Rehnquist wrote.

“Simply having religious content or promoting a message consistent with a religious doctrine does not run afoul of the Establishment Clause,” Rehnquist said.

In his dissent, Stevens said he believes the establishment clause “has created a strong presumption against the display of religious symbols on public property.”

The majority’s opinion in the case “makes a mockery of the constitutional ideal that government must remain neutral between religion and irreligion,” Stevens wrote.

The rulings were the first by the high court on Ten Commandments displays since it ruled in the 1980 Stone v. Graham opinion such presentations in Kentucky schools were unconstitutional.

Some opponents of strict separation said the decisions did not signal the end of the debate.

“[T]hese rulings only go part way in affirming that the Constitution allows government acknowledgments of America’s religious heritage,” said Alliance Defense Fund Senior Counsel Jordan Lorence in a written release. “We’ve always believed that no single case or two is going to settle this once and for all.”

Land said of the Kentucky courthouse decision, “If we allow the continuation of the brazen power grab of this judicial oligarchy masquerading as a Supreme Court, it will fundamentally alter our freedom and liberties. It is time for the American people to rise up and demand that we want government of the people, by the people and for the people back. We have not ceded our freedom and liberty to the imperial Supreme Court.”

–30–